The German “Templers” colonies in Israel

Visit our deep dive into German Colony Jerusalem and German Colony Haifa, key parts of German Colony Israel heritage. Discover Templer architecture, old-town charm, and stories from early settlers. After that, take a journey to Sarona Tel Aviv — blending colonial history with contemporary urban buzz. Ideal for travelers, architecture fans, and history lovers seeking hidden gems in Israel.

Written by Zvika Gasner 12-December-2024 (Originally 14-August-2019, updated 10-November-2020) photography by Angela Hechtfisch

The “German Colony” Introduction

The “German Colony” — or “German villages,” as they’re sometimes called — are now vibrant neighborhoods in several Israeli cities. They were founded in the late 19th century by members of the German Temple Society, known as the Templers. This Protestant group broke away from the Lutheran Church in 1858 after being expelled for their millennial beliefs. Their mission was to bring the prophetic visions of Israel’s prophets to life through everyday work and community living in the Holy Land. The name “Templers” reflects their belief that the human body is God’s temple, and that good deeds and moral living would help usher in the coming of the new Messiah.

In the mid-19th century, members of the Templer sect from Württemberg, Germany, founded their first colonies in Haifa and Jaffa. Later came Sarona (now part of Tel Aviv), Wilhelma (today Bnei Atarot), and Jerusalem. The second wave of settlements, established in 1906, included Bethlehem of Galilee and Waldheim (now Aloney Abba) in the Jezreel Valley.

They built homes inspired by traditional German farmhouses — one or two stories with slanted red-tiled roofs and wooden shutters — but adapted them to local conditions, using stone instead of wood or brick. Basements were used for storage, the ground floor for daily living, and the upper floor for sleeping.

The colonies were neatly organized along two main streets, and most residents worked in agriculture or traditional crafts like carpentry and blacksmithing. Sarona stood out as the first settlement devoted entirely to farming.

WW2 and the German colonies

After years of prosperity, the German villages faced a dramatic twist during World War II. Under British Mandate rule, both the British authorities and the local Jewish community found themselves at war with Germany — the Templers’ homeland. Although only about 20% of the Templer community supported the Nazi party, and around 500 joined the German army, the entire population was soon viewed with suspicion.

As tensions grew, relations with the Jewish community deteriorated. The colonies were placed under isolation, and many residents were later detained. Eventually, most were deported to Australia — then a British exile colony — while others were exchanged for Jewish Holocaust survivors from Hungary during the war.

After World War II ended and the State of Israel was founded, all Templer lands and properties were nationalized by the new Israeli government. Sarona, for example, became part of the HaKirya military complex, while other estates in cities across the country were converted into government offices.

In the 1960s, Israel and Germany signed a compensation agreement for Holocaust survivors — and as part of that deal, the Templers received 13 million dollars in compensation for their lost properties in Israel.

NOWADAYS: Tel Aviv “Sarona” German Colony

From a tourist’s point of view, Sarona in Tel Aviv is a must-visit spot. Located right in the city center, next to the HaShalom train station and Azrieli Center, it’s a chic, car-free promenade with beautifully restored streets that keep the original Templer layout.

The historic houses now host stylish restaurants, lively bars, and boutique shops — blending old-world charm with modern city vibes. At the southern end, you’ll find the famous Sarona Market, an indoor food paradise offering everything from gourmet dishes to exotic street food, perfect for dining in or taking away.

The American–German Colony in Jaffa

The American–German Colony, in the northeast part of Jaffa, sits between Eilat Street, Elifelet Street, and Jerusalem Boulevard. It was founded in 1866 by members of the American Protestant Christian Restorationist movement — a group that believed settling in the Holy Land would help bring about the coming of the Messiah.

Arriving on a ship called the Nellie Chapin, they brought wooden houses and supplies all the way from Maine, USA. But soon after landing, disaster struck. Many fell ill or died from plague after being forced to camp on an open Muslim cemetery, and they struggled with the harsh local climate and the unpredictable Ottoman authorities. Within a short time, most of the settlers gave up and returned to America — leaving behind only one person who stayed.

Three years later, in 1869, the German Templers discovered the nearly deserted village and saw its potential. They purchased the abandoned houses, rebuilt the community — and this time, it thrived.

Their main industries were hospitality and tourism. They opened several renowned hotels, including the country’s leading Hôtel du Parc and the Jerusalem Hotel, which famously hosted German Kaiser Wilhelm II during his visit to Jaffa on October 27, 1898. (The Jerusalem Hotel served as lodging for the Kaiser’s staff.)

After eight years of meticulous restoration, the historic Jerusalem Hotel reopened in 2018 as Hotel Drisco, named after the Drisco brothers who originally built it. The German Colony also became known for its thriving businesses — transportation companies, pharmacies, grocery stores, and more.

The outbreak of World War II marked the end of the German Templer community in Jaffa — just as it did for their other colonies across the country.

Haifa German\Templer’s colony

In Haifa, the main street of the German Colony — Ben Gurion Avenue — is the beating heart of downtown nightlife. It’s lined with lively restaurants and bars, many inspired by the flavors of modern Arab cuisine.

At night, with the sparkling lights and the breathtaking view of the Bahá’í Gardens cascading down Mount Carmel, it’s an absolute must-see. The beautifully restored Colony Hotel, right in the center of it all, is one of the most charming places to spend the night.

“Wilhelma” (“Bney Atarot”)German colony

Wilhelma, now known as Bnei Atarot, is a quiet, pastoral village located right next to Ben-Gurion Airport. It’s best known for Villa Wilhelma, a charming boutique winery that turns into an elegant buffet spot every Friday — the perfect place to unwind and enjoy great food and wine.

Jerusalem Templer’s colony

The German Templer Colony in Jerusalem is probably the only one still fully alive and thriving today. Located along Emek Refaim Street — meaning “Valley of the Ghosts” — it’s a vibrant area where people still live, work, and stroll daily.

Some of the original buildings have been beautifully restored, like the northern wing of the Orient Hotel, while others remain in their authentic form. Many renovated homes now feature one or two added floors, blending old charm with modern life. The street, which leads to the old Ottoman-era train station, is well preserved and full of character — a perfect mix of history and city life.

“Waldheim” (“Aloney Aba”)Templers colony

Aloney Abba, formerly known as Waldheim — meaning “Home of the Forest” in German — lies about 20 km southeast of Haifa. The village was founded by the children and grandchildren of Haifa’s Templers, making it the next generation of the German colonies. Its location was both practical and sentimental, connecting Haifa — then a growing port and commercial hub — with other major towns in the Jezreel Valley, such as Nazareth and Tiberias.

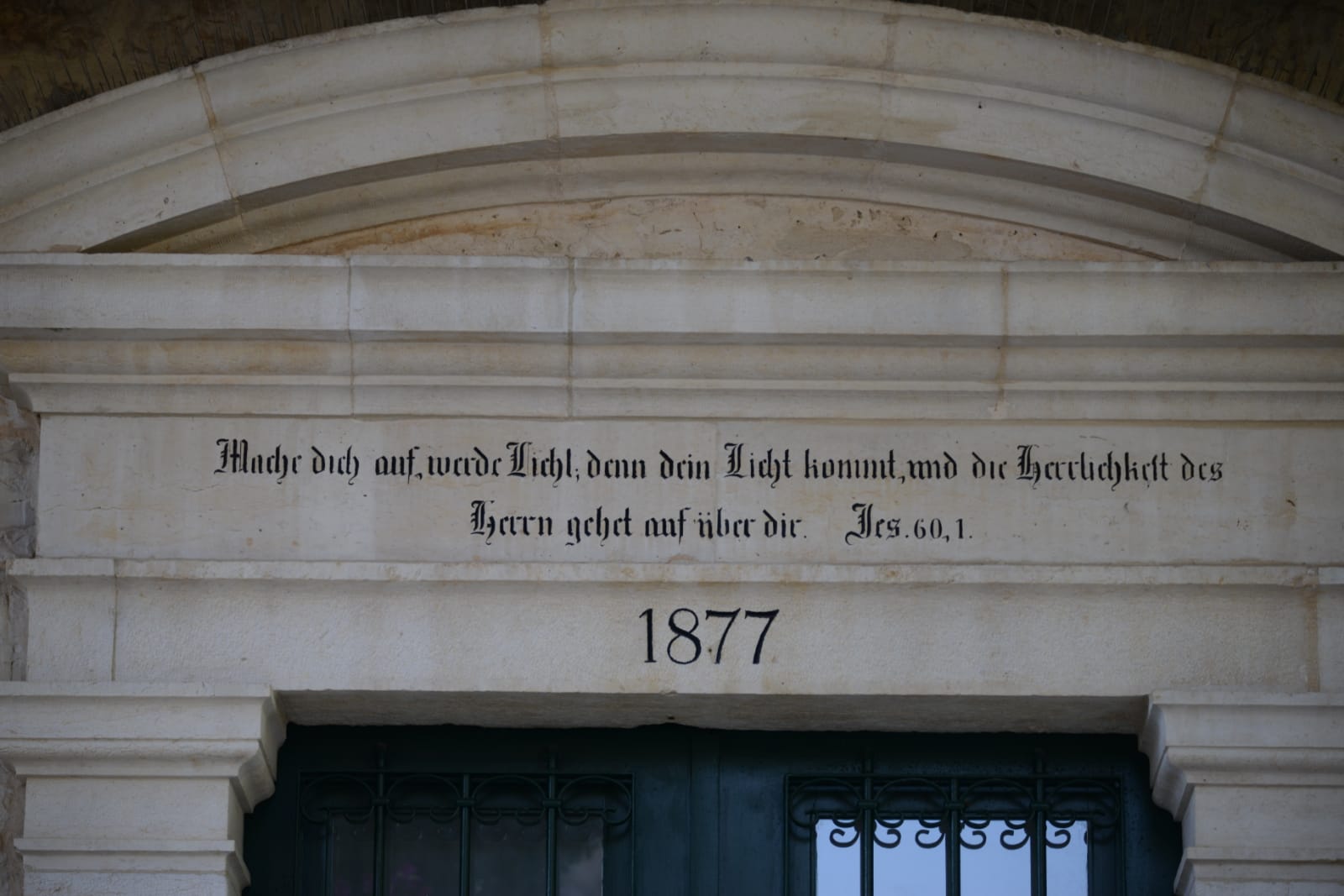

Today, this charming little village is beautifully maintained, surrounded by green parks and lush scenery. Many of the original Templer houses have been carefully restored. The historic Protestant church, once both a place of worship and a community center, is currently in need of support — especially from kind donors and Germany’s Foreign Ministry — to complete its renovation.

Next to the village lies the Aloney Abba Forest, known for its native Tabor oak trees. It’s a peaceful nature reserve, perfect for an hour-long circular walk surrounded by history and greenery.

Historically, during the late Ottoman period and into the early 1920s, oak forests once stretched continuously from the Jezreel Valley down to the Sharon plain — nearly 90 kilometers of dense woodland. Sadly, most of these forests were destroyed when the Ottomans cut down vast areas to fuel their steam trains. Today, only small patches remain, including a few symbolic Tabor oaks in Hod HaSharon. The forest of Aloney Abba survived only because the Templers of Waldheim and nearby Bethlehem of Galilee claimed ownership of the land and refused Ottoman attempts to harvest the trees — a decision that preserved one of Israel’s few remaining natural oak woods.

Bethlehem of the Galilee

To distinguish between the two Bethlehems in Israel, the one near Nazareth is called Bethlehem of Galilee — or Bethlehem of Zebulun, after the biblical tribe that once inhabited the region. In the Jerusalem Talmud, it’s also mentioned as Bethlehem Zoria, suggesting a connection to the ancient Kingdom of Tyre. Archaeologist Aviram Oshri has proposed that the name Zoria might actually be a mispronunciation of Noziria — meaning “Christian Bethlehem” in Hebrew. The more famous Bethlehem of Judea is, of course, the one near Jerusalem.

Because of its close proximity to Nazareth, some historians believe that Bethlehem of Galilee might actually be the true birthplace of Jesus. Dr. Aviram Oshri, a senior archaeologist with the Israel Antiquities Authority who led several excavations there, uncovered Jewish artifacts from the Second Temple period — including limestone vessels used exclusively by Jews for their ritual purity — alongside Christian remains from the Byzantine era (4th–5th centuries CE). These findings lend some support to his theory.

In the Gospel of Luke (2:1–5), it says:

“In those days a decree went out from Caesar Augustus that all the world should be registered… And Joseph also went up from Galilee, from the town of Nazareth, to Judea, to the city of David, which is called Bethlehem…”

Oshri argues that it would have been nearly impossible for a woman in her ninth month of pregnancy to travel the roughly 160 kilometers from Nazareth to Bethlehem of Judea. A journey of about 20 kilometers — the distance to Bethlehem of Galilee — makes far more sense. He suggests that the Gospel’s mention of Bethlehem of Judea was likely meant to emphasize Jesus’ descent from the House of David, fulfilling one of the key messianic expectations shared by both Christianity and Judaism.

However, not everyone agrees. Other scholars at the Israel Antiquities Authority have rejected this theory, and further excavations were halted due to funding cuts.

For centuries, Bethlehem of Galilee was home to only a small community — no more than about 25 Muslim families. Then, in 1906, a second generation of German Templers from the Haifa Colony established a new settlement here in the Galilee, also known as the Jezreel Valley.

Their reasons were both practical and spiritual. The location was ideal — a strategic crossroads between Haifa and Nazareth — and the Templer engineer and architect Gottlieb Schumacher, who was also a passionate amateur archaeologist, believed this was the true birthplace of Jesus.

The new colony became a sister settlement to nearby Waldheim (today’s Aloney Abba) and quickly grew into a thriving agricultural community.

By August 1939, about one-fifth of all German Templers in the country had joined the Nazi Party. When World War II broke out, the British authorities in Mandatory Palestine declared all Germans “enemy aliens.”

Many were placed under house arrest in Sarona (now part of Tel Aviv) and in Bethlehem of Galilee. In the summer of 1941, most were deported to Australia, while in 1942, women and children were sent back to Germany to reunite with their families.